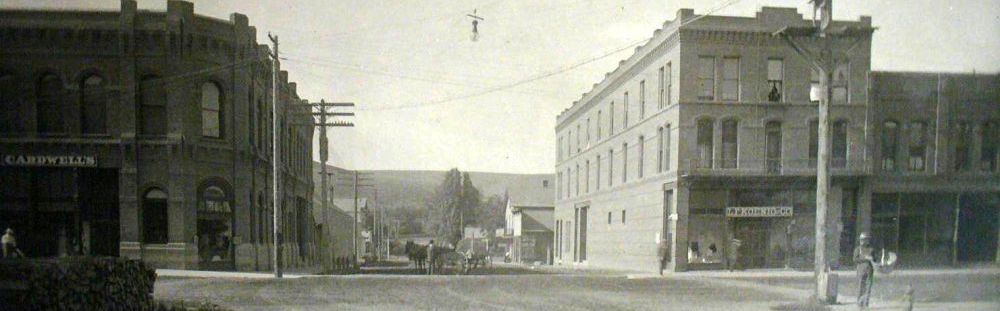

Pomeroy Washington Downtown National Historic District

News from the

May 1, 1985

Page 6

CCC Camp

"I was out of work. You couldn't buy a job if you had a million dollars," Clarence Schilling said of his reason for joining up with the Civilian Conservation Corps back in 1933. Living in the town of Bunker Hill, Ind., a town the size of Pomeroy, he said, "You couldn't find any work at all back home."

Youth were needed out west for reforestation, but only men under age 25 were accepted into the CCC program. Needing the work, Schilling and his mother had to lie about his age so he could be accepted, since he was 26.

Schilling said he was ready to go a week ahead of time. "I could hardly wait to get out of town." he said.

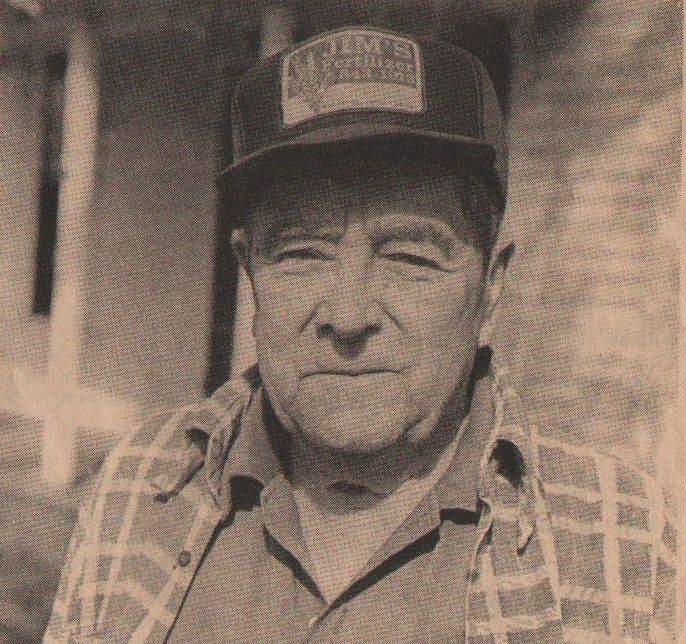

Clarence Schilling

The first stop was Fort Knox, Ken., where Schilling was given his physical, shots, clothing and orientation. After two weeks, he and other men were sent out to Whitney, Calif. However, because there were more men than were needed at that camp, some were given the opportunity to go to another location in California. Greeted by cold, frozen weather there, he volunteered to be transferred to another camp.

He was sent to Camp Trabucco, the present-day El Toro Marine Base, near San Juan Capistrano. The men had the opportunity to watch the swallows return to Capistrano, he said.

Schilling was given the job of truck driver, while the others did work building firebreaks and trails, After spending the winter there, he was transferred to a base in Idaho, near Coeur d'Alene. It was there that he was given the official title of Army truck driver. He make frequent trips into Coeur d'Alene for groceries and mail, as well as to Kellogg, Wallace, and Ft. George Wright in Spokane. Because the camp was in the center of nine logging camps, he would also bring supplies to the loggers.

"Boy, they sure went through a lot of beer," Schilling said of the loggers. He had to take his truck to Spokane each week for inspection. "I hated that," Schilling said, as each time he would return with his truck covered in mud, which would have be cleaned off.

One advantage to driving the truck in Idaho, he said with a laugh, was being able to stay out of the noxious weed evident in that area the other men had to work in.

All of the Coeur d'Alene camp moved down to Pomeroy in October 1935. Schilling said the Idaho camp had been a summer camp, with the men living in tents. About 200 men moved to the camp known as Camp Garfield.

His first impression of the area was not especially favorable. "Boy that was a night to remember," he said. "If there had been a freight train, I would've left," he kidded.

When he arrived in town, with a truck load of blankets, the ground was completely frozen. Then, he said, it "chinooked", dumping one and a half inches of rain and burying everything in mud. By the time summer came on, he had become accustomed to the area and its weather, and liked its climate.

Schilling did all of the hauling for Camp Garfield. There were forestry drivers at the camp, but he was the only Army driver, so he carried the mail and supplies for the men, The headquarters were in Lewiston, located where Lewis & Clark State College is now while the warehouse was near the river.

His schedule varied, depending on where he had to go that day. Sometimes he would have to be up at 3 a.m., to perhaps help to move camps into Idaho, while other days he would be hauling supplies out of Lewiston. Schilling said if there was no particular destination for him that day, he might do maintenance work on his truck or "swat flies in the mess hall".

Other times, Schilling might transport men, such as the night he took a group to the Lewiston Round-up. "That was a night," he said.

At that time, the Lewiston Main streets were not the one-way that they are today, and traffic was slow. After dropping the men off at the Round-Up grounds, Schilling had to drive the truck up to the headquarter grounds for parking. Traffic was bumper-to-bumper, would move a car-length then stop. He said it was early in the morning before they finally made it back to camp.

The men played baseball and football, and Schilling played for the town baseball team for one or two summers, with men such as Johnny Sparkman and his brother and Frank Hall. He also enjoyed ice skating, something he used to do in Indiana. Living eight miles from the city of Peru, he and his friends would ice skate up the Wabash River to the city, to watch a movie at the theatre. After the movie, they would take a short nap on the floor to prepare them for the skate home. At Camp Garfield, an ice rink was scooped out, flooded, and frozen over. "We skated there for weeks. That was my sport," he said.

While driving the Army truck coming from Coeur d'Alene, Schilling said a doe crawled up a high, steep bank. However, the fawn that was with her fell, unable to make the climb. The men in the back of the truck grabbed the fawn, fed and raised it, naming it "Ida". "So we had a mascot," he said. "She was real cute."

When the camp moved down from Coeur d'Alene, Ida came with it. She stayed with the mess sergeant, who kept his door open for her. Schilling said one day when the game commission visited, the captain told them if they wanted her, they would have to catch her. But the wardens were unable to catch her.

Ida would often tantalize the dogs, he said. She would run along a fence for about 400 yards, with the dogs chasing behind her, then leap the fence to the other side. The dogs would have to go back the length of the fence to get to the other side, then she would jump across again. Ida began to wander off for days, then weeks at a time and eventually disappeared altogether, Schilling said.

Schilling requested a discharge from the camp in 1936, after three years with the CCC. He returned to his home in Indiana, working with his father. All the while, he kept in touch with Cecile Schafer, a Pomeroy girl he had met while he was at Camp Garfield.

He returned to Pomeroy in the spring and married Cecile. He said he enjoyed Garfield County and had come to know the country here. He also had become acquainted with the people.

Schilling and his wife have five children and six grandchildren. Son Bud works at the post office in town, while daughter Mary is also in town, working at Dr. Shirley Richardson's office; son Charles works for the Corps of Engineers in Walla Walla; son Phillip is a law enforcement officer in Denver, Colo.; and daughter Phyllis is married to Jay Jardee and living in Seattle.

After coming to Pomeroy, Schilling got a job working for Jay Foster at his creamery, where he remained for more than 10 years. In 1949, he went to work for the county, until he retired in 1976.

Although Schilling hasn't run into any of the other CCC men for some time, he still sees the local men. He likes what the alumni association of the CCC is trying to do, in reactivating the program. "I think it would be a good deal," he said.

He said he learned from the experience in being with the CCC, travelling around and seeing the country.

"I enjoyed it all right, or I wouldn't have stayed as long as I did," Schilling said. "I wouldn't do it again, but I wouldn't take a million dollars for the experience.

oo O oo